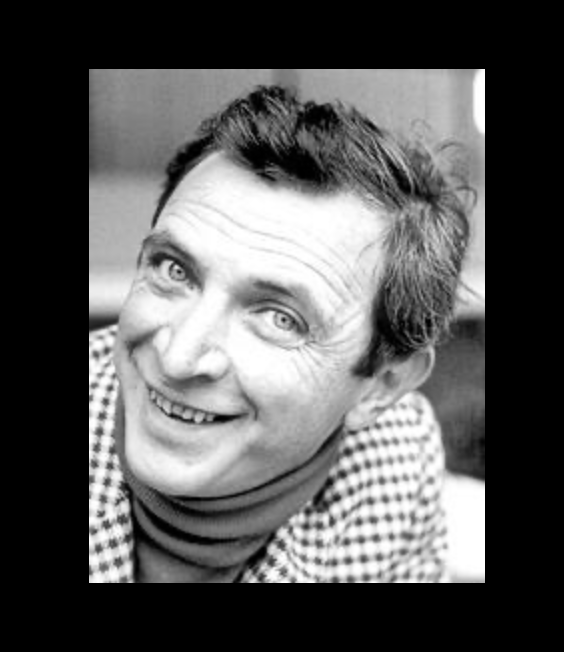

John Cranko was a South African ballet dancer and Choreographer who worked with the Royal Ballet and the Stuttgart Ballet.

This post may contain affiliate links, which means that the owner of this website will get a commission from any qualifying sales.

John Cyril Cranko was born on the 15th of August 1927 to parents Herbert and Grace Cranko in Rustenburg South Africa. As a child, he would put on puppet shows as a creative outlet for himself.

He received his early ballet training in Cape Town under the Famous ballet teacher and director Dulcie Howes.

In 1945 he choreographed his first work using Stravinsky’s Suite from L’Historire du Soldat for the Cape Town Ballet Club. By the time he reached London in 1946, Cranko had produced a handful of apprentice works, and when he joined Saddler’s Wells Theatre Ballet (Later called The Royal Ballet) in that year it was evident that his gifts were ideally suited to the needs of the newly-formed company which was to be a cradle and nursery for interpretative and creative talent.

Within four years, John Cranko was named resident choreographer of the troupe, and he made some of his finest early ballets for the Wells dancers including, Beauty and The Beast (1949), Pineapple Poll (1951), and Harlequin (1951).

Here is some of Pineapple Poll.

You can purchase his entire ballet collection by clicking here.

In 1950, John Cranko was asked to create a ballet for the New York City Ballet then visited Covent Garden, and he produced The Witch to the Ravel G Major piano concerto.

During the rest of the 1950s Cranko created works for both the Covent Garden and Sadler’s Wells branches of the Royal Ballet, notably Antigone (1959), Bonne Bouche (1952) for Covent Garden and The Lady and the Fool (1954) for the Wells.

In January 1954, Sadler’s Wells Ballet announced that Cranko was collaborating with Benjamin Britten to create a ballet. Cranko devised a draft scenario for a work he originally called The Green Serpent, fusing elements drawn from King Lear, Beauty and the Beast (a story he had choreographed for Sadler’s Wells in 1948), and the oriental tale published by Madame d’Aulnoy as Serpentin Vert. Creating a list of dances, simply describing the action and giving a total timing for each, he passed this to Britten and left him to compose what eventually became The Prince of the Pagodas for Svetlana Beriosova and David Blaire at Covent Garden.

But Cranko’s energy eventually needed greater opportunities than those offered by the Royal Ballet, so he produced two reviews Cranks (1955), which ran for 223 performances with a cast including singers, and New Cranks (1960). The New Cranks were not as well received as the first Cranks.

He also made two ballets for the Rambert Company, La Belle Helene for the Paris Opera Ballet and the Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet for the ballet of La Scala, Milan.

In 1960, Cranko directed the first production of Benjamin Britten’s opera A Midsummer Night’s Dream, at the Aldeburgh Festival. When the work had its London premiere the following year at Covent Garden, Cranko was not invited to direct, and Sir John Gielgud was brought in.

After being prosecuted for homosexual activity, Cranko left the UK for Stuttgart, and in 1961 was appointed director of the Stuttgart Ballet where he assembled a group of talented performers. Cranko was to find the ideal outlet for his energies and he molded a company, a school, and a repertory, that were to bring the Stuttgart Ballet vast international acclaim.

He started with Marcia Haydée as his prima ballerina, with Ray Barra, Richard Cragun and Egon Madsen as his principal men. He also used Birgit Keil, a young native-born ballerina.

Cranko’s company was loved wherever it played. For his company, Cranko continued to produce the full-length ballets which revealed Marcia Haydée as a superlative dramatic lyric artist. He did Romeo and Juliet in 1963, Onegin in 1965, Carmen in 1970, and the hilarious Taming of the Shrew in 1969, which Haydée and Cragun were the ideal Kate and Petruchio.

He also perfected the staging of the classics, which he felt so necessary for the development of his company, remounting Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, and acquiring Peter Wright’s version of Opus 1 and Brouillards are fine examples.

The initials RBME (the initials of Richard Cragun, Birgit Keil, Marcia Hadée, and Egon Madsen) seem central to Cranko’s personality, a declaration of the love and affection he had for his dancers, which they so warmly and totally reciprocated.

Cranko’s work was a major contribution to the international success of German ballet beginning with a guest performance at the New York Metropolitan Opera in 1969. At Stuttgart, Cranko invited Kenneth MacMillan to work with the company, for whom MacMillan created four ballets in Cranko’s lifetime and a fifth, Requiem, as a tribute after Cranko’s death. At Cranko’s instigation, the company established its own ballet school in 1971; it was named after John Cranko in his honor in 1974. His assistant and choreologist Georgette Tsinguirides preserved his works in Benesh Movement Notation.

Cranko died on the 26th of June 1973 bringing his company back from a triumphant season in New York. He suffered an allergic reaction to a sleeping pill he took during the flight.

The flight made an emergency landing in Dublin where Cranko was pronounced dead upon arrival at a hospital. His mother, Grace, who lived in what was then Rhodesia, learned of his death from a radio broadcast.

John Cranko was buried at a small cemetery near Castle Solitude in Stuttgart.

Nevertheless, his great talent, his great humanity, his humor, and the love he inspired in everyone who knew him, are still a part of the fabric of the Stuttgart Ballet, and they continue to give the company a special luster and appeal.

In 2007, the Stuttgart Ballet celebrated what would have been Cranko’s 80th birthday with the Cranko Festival. The ballet Voluntaries by Glen Tetley was created in his memory. The John Cranko Society in Stuttgart, founded in 1975, promotes knowledge of ballet and Cranko’s work, supports performances and talented dancers, and each year presents the John Cranko Award.

What a beautifully written and informative article on John Cranko’s life and contributions to the world of ballet! It’s incredible to see how his creativity and passion not only shaped the Stuttgart Ballet into an internationally acclaimed institution but also left a lasting impact on the art of dance itself. His ability to blend narrative storytelling with innovative choreography in works like Romeo and Juliet and Onegin truly set him apart as a visionary in the field.

The article also does a fantastic job of highlighting Cranko’s deep connection to his dancers and his dedication to fostering talent, as evidenced by the creation of the John Cranko School. His legacy continues to inspire, and it’s heartwarming to see how his humor and humanity were so integral to his relationships and creative process.

I’m particularly intrigued by Cranko’s work on The Taming of the Shrew. How did he approach balancing the comedic and dramatic elements in his choreography? Also, do you think his time in Stuttgart allowed him more creative freedom compared to his earlier career in London? I’d love to hear more about the ways his personal experiences influenced the emotional depth of his ballets. Thank you for shedding light on this remarkable artist!