Vaslav Nijinsky Biography

Vaslav Nijinsky is one of the most famous male ballet dancers to ever have graced our planet, so that is why I couldn’t have a ballet blog without at least having a Vaslav Nijinsky biography somewhere on it.

Even though we have only the testimony of eye-witnesses and the frozen images of a few photographs of Nijinsky from the past, with absolutely no video footage of him actually dancing, with the evidence that does exist there can be no doubt that Vaslav Nijinsky raised the art of dance to a whole new level and turned the development and the direction of ballet into fresh and fruitful new avenues.

This is a shortened Vaslav Nijinsky Biography, although it is still quite a long article.

Vaslav Nijinsky

His Early Childhood:

The Vaslav Nijinsky Biography starts with his birth in Russia, Kiev in 1890. At this time in history, Russia was an ideal spawning ground for dancers and choreographers with genius minds.

At this time ballet had a history of about 300 years, from its courtly beginnings in Renaissance Italy to France where it moved from the ballroom into the theatre. Their ballet acquired a set of basic principles from influential teacher and ballet master Jean-Georges Noverre.

A while later ballet creativity shifted to St. Petersburg, the capital of Imperial Russia.

The Imperial School of Ballet that Nijinsky attended was established in St. Petersburg in the eighteenth century with a corps of teachers recruited from Western Europe.

This school along with the ballet company at the Maryinsky Theater which it nourished became the great pride of Russia’s aristocracy, and lots of money was spent to make Russian Ballet the greatest in the world. By the 1870s its supremacy was unchallengeable.

In continuing with our Vaslav Nijinsky Biography, when he was ten years old in August 1898, he applied for admission to the St. Petersburg ballet school.

Nijinsky was the second of three children born to Thomas and Eleonora Nijinsky. They were both Polish and both dancers. The family led the life of nomads, as they journeyed from one engagement to the next across the vast extent of Imperial Russia.

Vaslav Nijinsky had an older brother, Stanislav, who was mentally retarded, and a younger sister Bronislave, who also became a distinguished choreographer in her own right.

Nijinsky’s parents separated shortly after his sister’s birth and his mother settled in St. Petersburg and took in boarders to make ends meet. Vaslav’s only hope to escape his poverty-stricken life was to enter the Imperial School of Ballet and train for a career at the Maryinsky Theater.

Life At the Imperial School of Ballet:

Nijinsky was accepted as a pupil in 1898 and almost at once, he showed the promise of a potentially great dancer.

The discipline at the school was strict and spartan and Nijinsky couldn’t wait to finish there.

He displayed rare gifts for dancing and mime and he studied under Legat, Gerdt, Oboukhov, and Cecchetti.

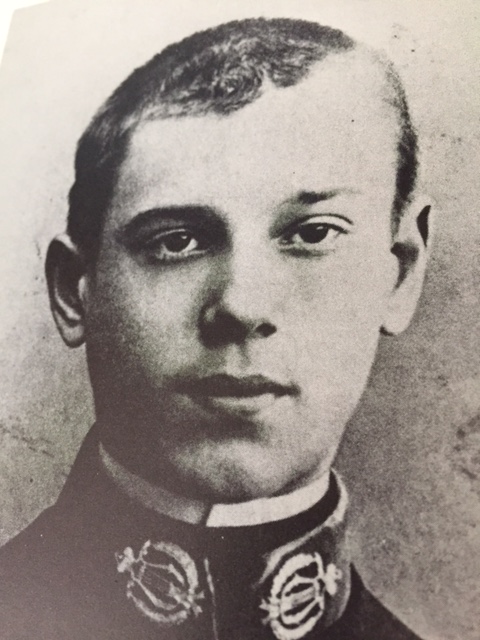

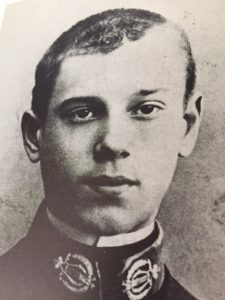

The picture on the right is him in his School uniform at age fourteen.

He was first noticed in 1905 when he danced a faun in a student performance of Fokine’s Acis and Galatea. Three years later at his official debut, he created a great impression in Mozart’s Don Giovanni after having already created the part of the slave in Fokine’s Le Pavillon d’Armide.

When he was in his early teens he started appearing in small roles at the Maryinsky. One of these as that of the mulatto slave in Petipa’s ballet Le Roi Candaule. He was eighteen at the time and danced during the Christmas season of 1906. His boyish grace illuminated a series of photographs done at the time and contrasted sharply with a picture of Nijinsky in his street clothes.

On his graduation the following spring, he was described by Alexandre Benois as a short, thick-set little fellow with the most ordinary and colorless face. It was only on the stage that Nijinsky was transformed and came alive.

After his graduation performance, Prima ballerina Matilda Kchessinskaya came to congratulate him backstage and requested him as her new partner. With her patronage, it meant that many doors would open for the nineteen-year-old prodigy.

Now that he was free from the chains of the school and when the Maryinsky closed from May to September, he could now do as he pleased, and even the remaining eight months of the year, in the evenings that he didn’t have to dance he could do as he wished. This new-found freedom went to his head, and he started burning the candle at both ends with his new aristocrat and millionaire friends.

Vaslav Nijinsky Biography Early Adulthood:

It was during this time that Vaslav took an interest in two girls from the Maryinsky corps de ballet, but even with these flirtations, it was with a well-known homosexual, Prince Paul Dmitrievitch Lovov that Nijinsky formed his first close relationship. They were seen together in all the best places.

It was through the prince that Nijinsky met Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev. This man would provide focus to his life and set him on the course to immortality.

Diaghilev was Nijinsky’s elder by sixteen years. He was born in 1872 into an aristocratic family. He had already made his mark in St. Petersburg as a catalyst, organizer, and patron of the arts, and he had edited and published an influential magazine with the latest artistic news events.

By the time Diaghilev and Nijinsky met in 1908, Diaghilev had come to appreciate ballet. His first loves had been music, painting, and poetry, but Alexandre Benois had convinced him that ballet was an art form worthy of serious attention.

Diaghilev started working on the forthcoming ballet season with his collaborators Benois Fokine, the painter Leon Bakst and Igor Stravinsky the composer. His genius for marshaling great talent was coming into full bloom. He specialized in making painters, musicians, poets and dancers work together to make the magic happen.

During this time Nijinsky was still just one of the several talented Maryinsky soloists and he was not yet the toupe’s undisputed star. After the close of the St. Petersburg season on the 1st of May, Nijinsky and his colleagues set off by train for Paris. On the 19th of May 1909, Paris got its first glimpse of the Russian Dancers and it was instant adoration.

The vitality and virtuosity of the male soloists stood out for them as it was new to them, and Nijinsky in particular elicited gasps of astonishment. Before this the female dancers had gotten all the acclaim, now it was finally the turn of the male dancers.

By June, Nijinsky and Diaghilev had formed a special attachment, and at the end of the Paris season when Nijinsky fell ill with typhoid fever, Diaghilev rented a furnished flat and took charge of nursing the patient back to health. From then on they were inseparable. The relationship blossomed into a creative partnership of far-reaching consequences.

Vaslav Nijinsky Biography Continued – He Becomes A Star!

With Nijinsky’s increasing popularity, Diaghilev had a problem. All the graduates of the Imperial Ballet School were obligated to dance at the Maryinsky for a minimum of five years after leaving school. He was now Diaghilev’s most acclaimed star and constant companion.

When Nijinsky danced Giselle for the first time at the Maryinsky in January 1911 his costume caused offense. To our eyes today, Benois’s design hardly seemed daring at all, but in those eyes back then it appeared excessively revealing.

Nijinsky refused to alter it in any way and the next day he was given an ultimatum – apologize or resign. He resigned of course. To this day we are not 100 percent sure if this was planned by Diaghilev to get Vaslav out of his contract early.

Les Ballets Russes de Diaghilev made its debut on the 9th of April 1911 at the Opera House in Monte Carlo.

Diaghilev had imported dancers from all over Europe, including teacher Enrico Cecchetti. Enrico’s classes imposed a new style and attitude on the dancers that weren’t drawn from the Imperial Theaters.

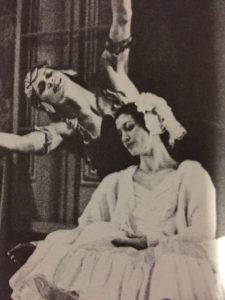

Fokine’s Le Spectre de la Rose was the most popular piece in the Diaghilev repertory and Nijinsky gave the perfect illusion of something non-human in his portrayal of a rose spirit. The dancer made his final leap through an open window and it was described as ‘a jump so poignant, so contrary to all the laws of flight and balance, following so high and curved a trajectory, that I shall never again smell a rose without this ineffaceable phantom appearing before me.’

Nijinsky answered somebody who asked him if it was difficult to stay in the air when doing his jumps – ‘No! No! Not difficult. You have to just go up and then pause a little up there.’

He and Karsavina made this role famous.

In June the same year, another of Fokine’s finest creations was given birth to – Petrouchka. In his role of the ungainly puppet, Nijinsky achieved a miracle of transmutation. He seemed to enter the very soul of the character when he put on his costume – and this was Nijinsky’s greatest gift. He had now made the transition from feted prodigy to that of a serious artist.

In his role of the ungainly puppet, Nijinsky achieved a miracle of transmutation. He seemed to enter the very soul of the character when he put on his costume – and this was Nijinsky’s greatest gift. He had now made the transition from feted prodigy to that of a serious artist.

Diaghilev’s company now began making the rounds of Europe. Nijinsky got the highest praises as the Sunday Times reported: ‘ He seems to be positively lighter than air, for his leaps have no sense of effort and you are inclined to doubt if he really touches the stage between them.’

Because running the world’s most prestigious ballet company was never a good financial endeavor, Diaghilev was forever attending elaborate receptions with Nijinsky in order to meet and flatter potential backers.

Other outrageous ballets were performed around this time that were not so popular with the public. These included LAspres-midi d’un Faun and Le Sacre du Printemps. Diaghilev almost seemed content that the public found the work distasteful. He was quick to understand the publicity value in hindsight. Even bad publicity is good publicity.

Fokine had by then departed from Ballet Russes due to artistic differences with Diaghilev, and Nijinsky was given the go-ahead to choreograph. The dancers battled to understand the young genius’s choreography and he and Diaghilev had many arguments in front of the company over this.

Vaslav Nijinsky Biography – His Rise and Fall From Grace

During the four years that Nijinsky worked under Diaghilev’s thumb, one has to wonder if he was content with his lot in life. To some, he seemed but a puppet of a master manipulator. He was constantly on the move through a world of posh hotels and even posher society, as well as being totally immersed in the problems and politics of the Ballets Russes.

He didn’t seem to have any true friends, as his relationship with the head of the company isolated him from comradeship with dancers within the company.

He seemed exhausted after putting on three path-breaking and unappreciated ballets and perhaps he longed for some form of escape which he showed in his works.

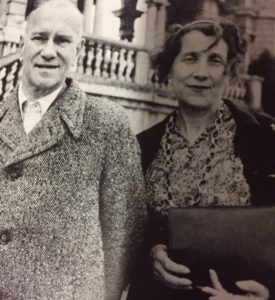

On the ship going to South America, Diaghilev stayed behind, and by the time the ship reached America, Nijinsky had formally proposed marriage to Romola de Pulsky who was traveling with the dancers in first class.

Four days after the ship docked on the10th of September Vaslav and Romola became man and wife.

Diaghilev took the news badly and he fired Nijinsky.

Unfortunately, his abrupt marriage to Romola and Diaghilev’s rejection was indirectly responsible for pushing Nijinsky across the borderline of insanity.

After he was rejected by Ballet Russes, a lot of propositions came his way, but none seemed to satisfy him. In the end, he took an eight-week season of ballet at a London variety theatre. He was to get his own dancers and choose the repertory.

Running a ballet company was unfortunately not Nijinsky’s forte, and the enterprise was plagued by mishaps from beginning to end. Nijinsky fell apart during the second week and his contract was canceled.

The Nijinsky’s returned to Budapest to await the birth of their first child, a daughter Kyra. They were overtaken by the outbreak of World War 1.

As a Russian subject, Nijinsky was technically a prisoner of war. The family was released in April 1916 and he and Diaghilev were reconnected in America. Even though Nijinsky seemed withdrawn, on stage he was better than ever.

Nijinsky acted as Artistic Director for Ballet Russes and his fourth and final ballet Tyl Eulenspiegel was created. There are very few photos that survived of this one, and it was followed by four months of travel across the length and breadth of the United States.

In June 1917, Nijinsky rejoined Diaghilev and the company for a series of performances in Spain. There was a lot of tension between Diaghilev and Nijinsky during this time as Diaghilev pressured Nijinsky to take tours that he didn’t want to do.

Nijinsky danced for the last time with the Ballet Russes in Le Spectre and Petrouchka on the 26th of September 1917 in Buenos Aires.

Vaslav Nijinsky Biography – Mental Illness

Signs of mental instability are said to have surfaced in South America, but it is not proven. A year later the Nijinsky’s had settled in St. Moritz to await the end of the war. Here Nijinsky was completely isolated from the ballet with its regular routines and structure. He began to sink into depression.

Early in 1919, Nijinsky agreed to give a private dance recital for friends and neighbors. Romola wrote that it was like watching a tiger that was let out of the jungle to destroy everything in its path.

Shortly after that he was examined by the distinguished Swiss Psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler and was diagnosed as an incurable schizophrenic.

Nijinsky was 31 years old and the next 31 he lived both in and out of asylums, sometimes better and sometimes worse, but never restored to what he once was.

Romola turned out to be a great support for him over the years, and she tried everything to move him out of his mental darkness. She even tried moving him to Paris in the hope that old association may help.

Nijinsky sadly died of an unsuspected kidney condition on the 8th of April 1950.

No other dancer, except Taglioni and Pavlova, has become so legendary during and after his lifetime, and no other male dancer of his generation could match him in the range of his powers though some, like Bolm, might make more impression in a particular direction.

His astonishing ballon, elevation, beats, and the quality of movement were unsurpassed, providing Fokine with the matchless material from which he fashioned the Golden Slave, Harlequin, Les Sylphides, Petrushka and the Spectre de la Rose.

Most especially, Nijinsky had the gift of merging himself completely in all his roles.

“The fact that Nijinsky’s metamorphosis was predominantly subconscious,’ wrote Benois of this phenomenon, ‘is, in my opinion, the very proof of his genius.”

To read more about other famous dancers, click here.