Turnout in ballet is a very controversial subject, and every ballet dancer wants to achieve perfect turnout. But how does turnout actually work and what are the limits. Let’s look at some of the muscle groups and ways in which we can increase our turnout in ballet.

Why is this and why do we need turnout in ballet?

There are three reasons we need to turn out in ballet.

The first reason is that turnout helps the dancer move sideways across the stage. In this way, the dancer can keep facing the audience in front of her as she moves effortlessly and elegantly across the stage.

The second reason we have turnout in ballet is because you can lift your legs higher when they are turned out. In ballet, the dancer aims to get her leg as high as possible without compromising her posture and hip alignment, and turnout is used to achieve this.

The third reason is that it looks aesthetically pleasing to watch a dancer with turnout. Turned in legs do not look at all attractive in ballet.

What is Turnout In Ballet?

Turnout is the outward rotation of your legs from the hip socket. Turnout in ballet can be used to describe the angle at the feet, the flexibility of the hip or the muscular control of that external rotation.

Although it is safe to imagine that the feet should perfectly reflect the available external rotation at the hip, in practice this is not exactly right.

Thomasen, who was a Danish orthopaedic surgeon, said in 1982 that the lower leg is externally rotated 5 degrees at the extended knee and that the normal ankle joint has an axis with an external rotation of 15 degrees. Therefore the foot lies at an angle of 20 degrees outwards. This is a bonus for classical dancers, but pushing beyond this at the knee or at the ankle when fully turning out the hip causes distortion of these joints with resulting malalignment of the foot.

Unfortunately once the joints are forced out of alignment, true balanced muscular control of the joint is lost.

So dancers need to be very careful to make sure that they are working within the range dictated by the hip joint, and only then can the externally rotated limb be securely controlled.

Turnout is not about standing and trying to force your feet into a 180-degree line as can be seen in Figure A. This is an impossible, over turned-out position.

Figure B shows a more realistic angle at which to work, but this position still demands at least 60 degrees of external rotation from the hip.

Figure C shoes a still visually acceptable angle at which to work, where a good balance of muscular control can be used around the hip.

When training young children, they need to work at an even more decreased angle to avoid injuring their joints over time.

Children dancing from the ages six to twelve years have the benefit of developing the femoral neck angle and after that can the bone shape no longer be altered.

To benefit from this, the child must presumably be working at her individual maximum with good control in order to generate the force withing the hip joint.

The entire leg is rotated outwards, and it is dependent on your flexibility in the hip socket as to how far you can work your turnout. When bending your knees, they should always align with your toes and when standing, your kneecap should face the same way as your foot is pointing.

The amount of external rotation in the hip is dictated by the shape of the bones involved and the flexibility of the ligaments, joint capsule, and muscles.

What Muscles Are Used In Turnout?

There are many muscles of turnout, some more important than others, and there will be a constant interplay between them depending on the position of the hip.

Teachers will need to find the best ways of teaching turnout. Some may emphasize the wrapping round of the upper thigh at the back and others may emphasize the flattening and rotating of the front of the thigh.

These are the muscles that are used and that will be activated during external rotation of the hip in classical ballet. How much they are activated depends on the position of the hip joint.

The first are the adductors (inner thigh muscles). Nowadays the majority of teachers believe these are the most important muscles and insist that they are used.

In first, third or fifth position of the feet when the thigh is is fully turned and the pelvis held in balance, the inner thigh is brought to the front producing a flatness and muscle delineation, which is evidence of control and increased stability.

If we consider that the pubis of the pelvis is the origin of the adductors and the insertion is down the line spear at the back of the femur and if the pelvis is well placed (neither tucked under nor arched), the adductors will pull the back of the femur round towards the front.

They will also adduct it (bring it in towards the centre), which is exactly what we want in our closed positions, from where we start and in which we finish.

The more anterior muscles of the adductor group also help with flexion, taking the hip into deviant positions.

So teachers need to continue teaching the importance of the adductors in holding turnout. These muscles need to work hard in all closed positions and closing movements in first and fifth.

Using the adductors of the supporting leg in adage will help the control of the supporting hip. However, in high adage positions to second when the pelvis has tilted horizontally, it is unlikely that the adductors are active on either leg. The adductors could well be holding onto turnout as they go through the motions of a grand battements a la second, but It is important that this muscle group develops strength to balance out the muscles on the outside of the hip.

The apparent decrease in knee problems in dancers over the past two decades could be due to better emphasis on the use of the inner thigh rather than the forcing of turnout from the feet.

The gluteus Maximus is the most superficial of the seat muscles and is an external rotator of the hip joint and will be more or less active throughout classical movement.

If it is over gripped in static positions, the pelvis will tuck under and the normal lumbar curve will flatten. Whan movement takes place, the gripping actions must relax and so control is thus lost.

The Gluteus Maximus is an important muscle which extends the thigh and turns it out, as in arabesque. Posturally it works with the hamstrings below and supports the spine above, but overuse disturbs fine control and upsets muscle balance around the hip.

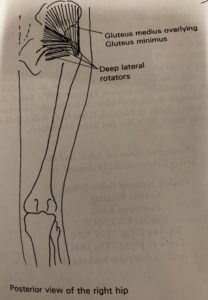

The third set of external rotators is made of the six deep lateral rotators (deep turnout muscles) situated closely over the back of the hip joint.

These can be thought of as the deeper layer of the gluteal muscles. This group is made up of the obturator interns and externes, gelmellus superior and inferior, quadrates femurs and piriformis. Their attachments strongly suggest that they are external rotators of the hip, but they are so deep that no EMG studies have been carried out on them.

However most dance investigators ad anatomists agree about the importance of the six deep lateral rotators in their role as turnout muscles.

So when standing on two feet in your ballet positions, the adductors, Gluteus Maximus and the deep turnout muscles will be well activated. In adage positions to second where the hip is abducted the deep lateral rotators come into their own.

As so much of our classical vocabulary is set in second positions, both a terre and en l’air, the full use of rotation and the dropping of the hip requires the use of these ideally placed muscles.

Remember that these are relatively small muscles and they will need to work concurrently with others to generate a burnout force around the joint.

The Sartorius is the long diagonal muscle which passes over the front of the thigh from the pelvis above ve the hip joint to the medial condyle of the tibia. It has a rotatory effect on the hip, although its main action is flexion, abduction and external rotation of the thigh at the hip and flexion of the knee like in a retire. The Sartorius works with the six deep lateral rotators in second positions.

The posterior fibres of the Gluteus medius and minimus also help with external rotation of the hip as the anterior fibres internally rotate.

Biceps femoris, the outside hamstring muscle, contributes to external rotation of the hip, pulling laterally on the head of the fibul where it inserts.

Another muscle that contributes to turnout is the iliopsoas, which is the main hip flexor. It is also an external rotator helping to hold the turnout in devant positions along with the adductors.

So as you can see there are many muscles of turnout, and some more important than others. There will be a constant interplay between them depending on the position of the hip.

While it is interesting to learn about the muscles of the hips, teachers cannot teach too analytically, but instead have to find the key to achieve the desired results.

How To Turnout In Ballet

Simply spreading your feet outwards as wide as they will go, as most beginners tend to do, is not correct, as you are simply placing a lot of strain on the knees, and this is going to cause injury in the future.

The best way to start is to find your natural turnout by standing with your feet in parallel first position, and then gently squeezing the buttocks muscles and letting your legs move outwards from the hip.

Once you are in natural turnout, there are many exercises that are done during your ballet class that work in turnout and train the muscles to remember this position and improve on it while you are dancing.

The more you dance in turnout, the stronger the muscles will get, and your body will allow you to do more as you get stronger. In the beginning, you will often feel your turnout slipping. Just stay focused on holding the turnout from the hips while you dance, and your body will eventually start doing it on its own.

Extra Note: When you turn out your legs for the first time you may find that one side can comfortably turn out much more than the other side. If this is the case, always work according to the rotation of the less supple leg. Never force turnout as this will lead to injury.

How Can I Improve My Turnout?

Most dancers dream of having 180-degree turnout, and unfortunately, this is just not possible on most body types. You can, however, enhance and improve on what you already have.

Remember, in order to be a good dancer or a professional dancer, there is a lot more than turnout that is needed, for example, musicality, technical strength, good feet – the list goes on…. Most gifted dancers do not have 180-degree turnout but still do very well for themselves.

If you start to dance as an adult, it is a lot harder to get your turnout as the hips have already set, whereas in a child the growing body is pliable and supple.

On this video, is one of the more popular exercises to stretch the turnout in your hips.

How To Increase The Turnout In My Supporting Leg

Here is an excellent exercise to do to increase the turnout in your supporting leg.

More Exercises for Your Turnout in Ballet

Tune Up Your Turnout In Ballet

Working rotation from the hips is important in all dance forms, not just ballet.

Here are two exercises to test your turnout and then end with a stretch.

Exercise No. 1

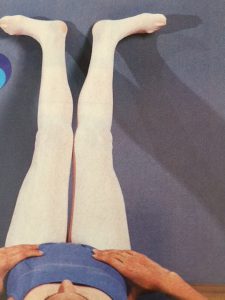

Lie on the floor with your hips about two feet away from the wall and place your legs at a 60-degree angle above the ground, resting your heels against the wall.

Hold your feet a few inches apart with your legs parallel to one another. Keep your knees straight.

Place your hands on your hips to make sure they remain still.

Working from this starting position, slowly rotate your legs out, initiating from the hips.

Working from this starting position, slowly rotate your legs out, initiating from the hips.

You will feel your inner thighs wrap forward and out like you should when standing in a turned-out position.

Without the floor under your feet, you won’t be able to twist your knees and angles to increase your turnout, you will be working only within your natural range.

Once you are fully rotated, return to parallel and repeat the rotation five more times.

Exercise No. 2

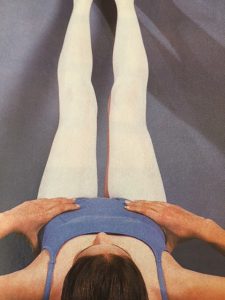

Lie on your side with your head resting on one arm and the other arm bent in front of you with the palm flat on the ground. Line up your shoulders, hips, knees and ankles so that you aren’t rolling forward or back.

Slide your knees forward so that they are slightly bent. Point your toes and keep them in line with your upper body.

Without changing the position of your torso, hinge your top leg like a door, opening at your knee and keeping your feet connected.

The rotators of your upper leg will be isolated as you work against gravity to lift your knee without disturbing your balance.

Hold your most turned out position for a few seconds before lowering.

Repeat 15 times then roll over and repeat on the other side.

If you really want to work those rotators repeat the exercise with a thera band tied around your legs just above your knees.

After working those rotators, stretch it out by sitting with one leg bent in front of you and fully extend your other leg behind you, aiming to keep your hips square.

Relax your upper body forward and feel a release in the hip of your front leg.

Hold for 30 seconds or longer and then repeat on the other side.

Correct control of turnout in ballet does not just happen. It needs to be careful tough, just as the position of the pelvis, alignment of the spine and weight placement through the foot need to be guided.

As the mother of four, and only one being a girl, I absolutely adore your niche! How adorable your images are!

A suggestion on the title, it was a bit confusing to read due to the redundancy of the word ‘Turnout’, I actually had to read it a couple of times to understand what i was reading, maybe use a synonym like “Retention’ or some other relevant term.

Your product reviews are excellent! Do you have access to any videos to share on your site? That would be something worth coming back for,for sure! To see those cute little feet learn and grow in their performance… wow!

I hope my feedback/comments help. Please let me know when you make updates to your site I would love to see where you go with it!

Thanks,

Teanna

Thank you for the suggestions Teanna.

Turnout Exercise the best.

Michel,

I’m considering getting my granddaughter ballet lessons, this post on Turnout is profound. Yes, when we rotate and raise our legs and train our muscles to Turnout, it’s certainly pleasing to the eye. And to face the audience while gracefully moving sideways is also a nice feature of Turnout, but the danger of injury in overturning the feet makes me aware of choosing a caring dance instructor with good qualifications.

JR

You are right to look for the right instructor, as the wrong training can cause not only bad habits but long term damage that only shows up a bit later in life.

As a child, I wanted to dance ballet; especially since it would help my posture. However, as I took classes, it turned out that each time they’d sat “left pointer, left heel, right pointer, right heel; I’d do the correct side but I’d do heel instead of pointer and vise versa. Why? I just couldn’t catch up.

Like anything, it takes lots of practice and repetition and patience.