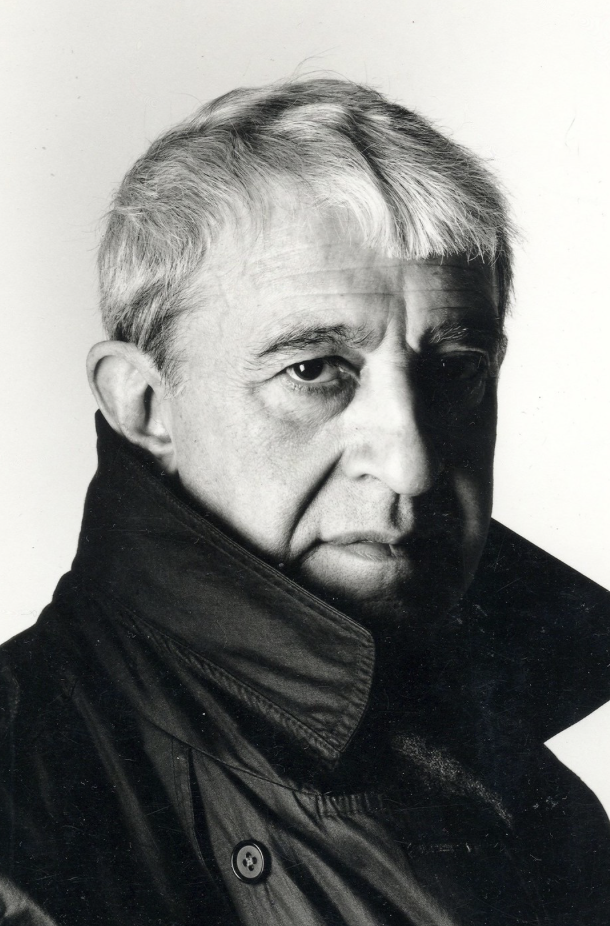

Let’s take a look at Kenneth Macmillan and how he influenced the world of ballet over the years. If you are wondering who he was, Kenneth MacMillan was the leading ballet choreographer of his generation.

Who Was Kenneth MacMillan?

He was born in a poor Scottish family in Dunfermline, Fife in 1929. He had a burning sense that ballet theatre should reflect contemporary realities and the complicated truths of people’s lives. He became director of The Royal Ballet and created some of the outstanding dance works of the twentieth century.

His parents, William and Edith MacMillan, had met in Norfolk where William was briefly stationed, en route to France, during the First World War.

After William, a coal miner, was gassed in the conflict, mining was no longer an option for him. He then tried and failed as a chicken farmer. The family fled the farm in the middle of the night (“a moonlight flit”) and went south to Norfolk, to live in Great Yarmouth, where William could only find occasional work during the Depression years of the 1930s.

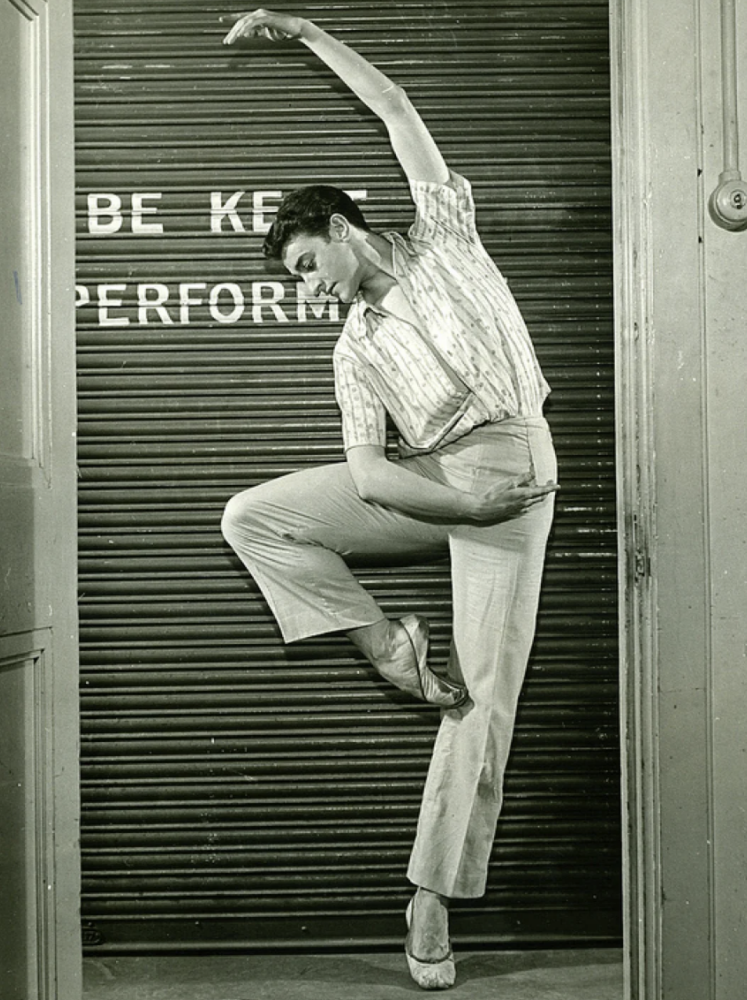

This was taken of Kenneth and His Mom Edith in 1932

This was taken of Kenneth and His Mom Edith in 1932

When Kenneth was 11, he won a scholarship to the local grammar school. The Second World War had begun and Great Yarmouth was repeatedly bombed by the Luftwaffe.

The school was evacuated to Retford in Nottinghamshire and it was here that he first discovered ballet. He had already learnt tap and Scottish country dancing and taken part in entertainments for soldiers at American air force bases. In Retford, he took tap lessons from Jean Thomas, a local dance teacher, who encouraged him to try ballet. He was soon obsessed and devouring back issues of The Dancing Times in the local library.

Edith MacMillan, who suffered from chronic epilepsy, died in 1942. Kenneth was emotionally devastated. ”I remember coming back for my first school holiday to Yarmouth, and was met at the station by my father and my sister, who told me my mother had died the previous night. From that moment on, I felt that I was on my own. I wasn’t very close to my father. We got on all right, but he was a rather strict Scottish gentleman, rather remote and unemotional, especially to me.”

A dance teacher in Great Yarmouth, Phyllis Adams, became, in effect his surrogate mother. She taught him for free and, in effect, shaped his ambitions. “She treated me as an adult, which was wonderful”, MacMillan said in a 1991 interview. “I didn’t know what I was going to do when I grew up until I met Phyllis Adams.” Adams realised that she had a prodigiously talented pupil and MacMillan created his first choreography on Adams’ daughter, Wendy and a friend. It was, she remembers “a duet with chairs to I love a Piano ”. “A lasting memory of mine”, she continued, was “watching Kenneth doing grand jetés across Yarmouth Market Place on his way home from school.”

When he was 15 he found an advertisement in The Dancing Times offering scholarships for boys at the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School. He wrote to Ninette de Valois in the name of his father.

The letter got him an audition which was participation in a class with the Sadler’s Wells Company. ”I was put between Margot Fonteyn and Beryl Grey and I was terrified, added to which I was screamed at, quite rightly, by Miss de Valois for being late for her class.”

Ninette de Valois was persuaded of his ability and awarded him a scholarship consisting of free tuition, an accommodation allowance and five shillings a week pocket money. At the end of term, MacMillan told his headmaster at the grammar school that he would be leaving, who in turn proudly announced the news at morning assembly. ”I was mortified,” MacMillan recalls. ”I fled the school that morning and never went back.”

At the Sadler’s Wells School MacMillan began to meet kindred spirits his own age. “It was the first time I was with people whom I could talk to about the things I really felt.”

In little over a year he was a member of the Sadler’s Wells Opera Ballet (later Theatre Ballet). Soon he moved to the larger Sadler’s Wells company, now based at Covent Garden. And he went on its first American tour, dancing the role of Florestan in the last act pas de trois in The Sleeping Beauty on the company’s triumphant opening night in New York in 1949.

He danced many leading roles and then moved to the Covent Garden Company in 1948. He returned to Sadler’s Wells in 1952 and made his apprentice ballets – Laiderette and Somnambulism for the Wells Choreographic Group.

But MacMillan was increasingly troubled by stage fright and this was an important reason why he turned to choreography. Somnambulism, his first workshop piece for a Sunday workshop under the direction of David Poole, showed evident flair. This sureness of touch was confirmed by Laiderette in the following year. But it was Danses Concertantes in 1955 that established him. The dazzling spicily witty inventions revealed that an extraordinary new choreographic talent had been found.

That same year he made his first dramatic work – House of Birds – a version of a Grimm fairy tale, following this in the next year with his first work for the Convent Garden Company – Noctambules (a dramatized version of the last act of The Sleeping Beauty).

This was a dramatic work about a magician in a back-street theatre who hypnotizes his audience so that they reveal their innermost feelings and desires. A faded beauty recaptures her youthful loveliness, a soldier revels in slaughter, an innocent girl is loved by a rich young man, and at the end the Magician is trapped in his own bizarre fancies.

All three ballets indicated an original talent, blessed with fluency of invention, and a refreshingly different – though entirely classical – choreographic manner.

All three ballets were also marked by an excellence of their design by Nicholas Georgiadis, introducing a collaboration which continued for years.

In these works, MacMillan was concerned to consolidate his knowledge of his craft. He returned to working for the Sadler’s Wells Theatre Ballet with two more ballets – The burrow (1958) which portrayed a group of people hiding from oppressors and the light hearted Solitaire (1956) ‘ a kind of a game for one.’

There followed another work for the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden, a version of Stravinsky’s Agon (1858) which extended his earliest faceted dance style in a study of a house of pleasure. It was a mysterious and beautiful piece, but it failed to find much favor with the public at the time.

He also made two ballets for America Ballet Theater in this year – Winter’s Eve, a story of a blind girl, and Journey, which treated the them of death with considerable success.

A major change in his style was announced with Le Baiser de la Fee, for Lynne Seymour (who was to become the Muse for many of his greatest ballets thereafter), Svetlana Beriosova and Donald MacLeary as his choreographic manner became softer and more expansive. The ballet was notable for the skill with which Kenneth MacMillan overcame the problems of staging what has always been considered a difficult work to realize, and also for the acutely sensitive way in which the choreography echoed Stravinsky’s homage to Tchaikovsky by offering a parallel homage to Petipa – particularly in the Mill Scene for Seymour and MacLeary.

The ballet was further distinguished by Kenneth Rowell’s decor, which arguable ranks as the most beautiful and poetic ballet designs seen a Convent Garden since the war.

Baiser was followed in December 1960 by MacMillan’s most assured and compelling dramatic work, The Invitation, and in the following September he made a piece of our dancing called Diversion.

With Rite of Spring in May 1962, he showed a new mastery in maneuvering large masses of dancers, and his next ballet, staged for the Stuttgart Ballet was Las Hermanas which was another plotless work and one of his finest (1963) when Symphony was staged at Covent Garden. It was a beautiful piece, and one of his most personal statements on what he felt about dancing, having a profusion of choreographic invention.

He returned to working with the Royal Ballet’s Touring Section in January 1964, making a pop-art version of Milhaud’s La Creation du Monde, and for the Shakespeare Quatercentenary Celebration in June of that year he produced Images of Love, a series of dance incidents, each inspired by a quotation from Shakespeare.

The work was uneven, but in two sections for Lynn Seymour (with Gable and Nureyev) he indicated a new plasticity of manner that was extremely impressive, and the ballet also provides an interesting hint of his reaction other than a written text, which was to be extended in his Romeo and Juliet the falling year.

IN June 1964 he created a work that he had long been contemplating, a ballet that has been recognized as one of his finest, The Song of the Earth. It was first staged in Stuttgart, and was enhanced there, as it was at its later staging for the Royal Ballet with Marcia Haydee as the woman.

For several years, MacMillan had ambitions to create a dance setting of Mahler’s Song of the Earth . But the board of the Royal Opera House felt that the score was sacrosanct. MacMillan’s contemporary and friend, John Cranko, the director of the Stuttgart Ballet, welcomed the opportunity to stage it. It was quickly recognised as one of MacMillan’s most intense and beautiful ballets.

In a radio interview before he died MacMillan said it was his favourite among his works. Throughout his career, Stuttgart provided MacMillan with artistic refuge, in 1976 it staged the intensely felt Requiem (to the Fauré score), another MacMillan ballet denied performance at Covent Garden – and for similar reasons to Song of the Earth .

In 1966 Kenneth MacMillan was released for three years by the Royal Ballet to take up the post of Director of the Ballet of the Deutsche Oper, West Berlin, where he was joined by Lynn Seymour as ballerina, and where he staged a variety of works, many designed to help shape and train his company.

Works like Valses Nobles and Concerto (1966). and Olympiade (1968) were all basically exercises in setting a somewhat raw company dancing with clarity and precision.

While in Berlin he also created two fine dramatic ballets – Anastasia in 1967 for Lynne Seymour, and Cain and Abel in 1968. He also mounted two classic stagings of an opulent The Sleeping Beauty (which preserved all the Petipa choreography but aimed at a more sensitive and logical production) in 1968, and a Swan Lake in 1969, his last gift to the company before returning to London preparatory to taking up the directorship of the Royal Ballet in 1970.

Many in the London’s dance world were resentful at what they regarded as the premature retirement of MacMillan’s predecessor, Frederick Ashton. Almost immediately MacMillan faced a financial crisis and was forced to lose some forty dancers from the strength of the two companies. Temperamentally MacMillan struggled with the demands of administration. Nonetheless in his time as director he greatly expanded the company’s repertory, doubling the number of Balanchine works, introducing ballets by Tetley, Cranko, Van Manen, and Neumeier. He also managed to persuade Jerome Robbins to come to London to stage Dances at a Gathering .

During the next seven years Kenneth MacMillan maintained an exceptional flow of new ballets in addition to his time-consuming duties as director of a major company.

In 1974 MacMillan married Deborah Williams, an artist who was Australian and together the couple had a daughter, Charlotte. His marriage gave him a new emotional security and helped steel his resilience.

Eventually in 1977, he was impelled by the need to devote all his energies to creativity, to give up the administrative post of Director of the Royal Ballet, remaining since then as chief choreographer.

During these years he produced three major full-evening ballets – Anastasia (1971), Manon (1974), Mayerling (1978) and a series of works which displayed the varied facets of his company’s talents including Rituals (1975) Elite Syncopations (1974), Four Seasons (1975), Triad (1973), The Seven Deadly Sins (1973), La Fin du Jour (1979), and several works for the Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet including The Poltroon (1972) and Playground (1979) as well as brief pieces like Sideshow for Seymour/ Nureyev and Pavane for Sibley/Dowell (1973), and supervising the staging of the Sleeping Beauty (1973).

Mayerling in 1978 was choreographically the richest of his three act ballets, it is a dark study in psychosis. Later works drew on a similarly dark palette; a disturbed family in My Brother my Sisters; fractious mental patients in Playground; Valley of Shadows included scenes in a Nazi concentration camp. Different Drummer told the story of George Büchner’s Woyzeck, another example of man’s inhumanity to man. And with the full-length Isadora, he sought to breach the barrier between ballet theatre and the theatre of the spoken word.

Further he produced two major creations for the Stuttgart Ballet, the tremendous setting of Faure’s Requiem in memory of John Cranko (1976), and the darkly erotic My Brother, My Sisters (1978).

Kenneth MacMillan was knighted in 1983 and in 1984, while remaining chief choreographer of the Royal Ballet, he became associate director of the American Ballet Theatre for some five years.

For ABT he staged two new works, Wild Boy and Requiem (to Andrew Lloyd Webber’s music)., in addition to staging Romeo and Juliet and creating a new production of The Sleeping Beauty.

The final years of his life were immensely productive. After a serious heart attack in 1988 he knew he was living on borrowed time. After a five year period in which he had not created a new work for Covent Garden, he returned in 1989 to make The Prince of the Pagodas , choosing the 20-year-old Darcey Bussell as his young heroine. For Dance Advance, a group of former Royal Ballet soloists, he created Sea of Troubles, a modern-dance version of Hamlet.

In the former Bolshoi principal dancer, Irek Mukhamedov, who joined the Royal Ballet in 1991, MacMillan found his final muse. For Bussell and Mukhamedov, he choreographed a gala pas de deux, which became the core of his ballet Winter Dreams, inspired by Chekhov’s play Three Sisters. The final ballet was replete with cameo roles for older dancers; Gerd Larsen, Anthony Dowell, Derek Rencher.

The Judas Tree, MacMillan’s dark parable of betrayal with Mukhamedov as its brutal anti-hero, was his final ballet.

According to Jann Parry writing in The Observer after his death, it was “an intensely personal work, tapping the murkiest streams of his ‘inner landscape’ in a way even he found frightening.”

Kenneth MacMillan died at the Royal Opera House on a night when Birmingham Royal Ballet was presenting his Romeo and Juliet in Birmingham, and when Mayerling was being revived at Covent Garden after a long break. The curtain calls were cut short by the news that he had collapsed backstage. The cast of Mayerling, still caught up in the drama of the ballet were numb with shock. There were gasps and sobs from the members of the audience, who stood in silence before filing out into the night – an astonishingly theatrical echo, Parry recalled, of the funeral scenes that conclude the ballet.

Kenneth Macmillan’s whole creative approach was concerned with the revelation of feeling through movement. He can, because he is a master of his craft, produce brilliantly effective Neo-classic choreography, and The Four Seasons testifies.

He could also make startling extensions of the academic dance, inspired by Japanese themes in Rituals, or by the imagery of the sporting life of the beau Monde of the 1930s in La Fin du Jour.

In Elite Syncopations he produced a ragtime frolic which set his Convent Garden cast dancing with ebullience and wit. The two major pieces made for Stuttgart – Requiem and My Brother, My Sisters, he could provide, in the first a gown of greatest sensitivity in the face of grief and death, and in the second, a macabre and thrilling exposition of sexual tension within a family.

For MacMillan was supremely the poet of passion, of dark unhappy desires and frustrations and self-deceits.

He could show us the gnawing appetites and needs, the loneliness and the sexual drive, that society most usually make behind superficial good manners.

MacMillan exposes it in burningly clear movement, acting as a phychoanialyst to his characters, forcing them inexorably into dramatic situations in which the truth of their feelings and sorrows must burst forth in expressive dance.

His Romeo and Juliet is as much a ballet about passion as The Invitation.

Rite of Spring showed a primitive community obsessed by the sexual urgency of a tribal ritual which must placate in divinities and guarantee the earth’s fruitfulness by the Virgin’s first orgasm, which is her death and the earth’s life. In his two historical ballets, Anastasis and Mayerlings, compass real events rather than merely literary sources or fairy tale, and in Mayerling he combined this with a piercing and detailed study of a man’s descent into despair and suicidal depression.

But one overriding fact must be stated. MacMillan’s only means of communicating his view of the world is movement, and movement based upon the classical tradition in which he grew up. This provices him with an inbuilt formal discipline which shapes, canalizes and guides his dance imagination.

All his ballets are classical, in that they develop and extend the range and possibilities of the academic dance D’ecole, no mater how far-ranging or extreme may seem their language, as in Rite of Spring or Rituals.

In this lies the strength of Macmillan’s craft, and the necessary foundation for his adventurous and highly poetic ballets.

Since his death his reputation has continued to grow. Audiences flock to his works, while dancers everywhere compete to perform in his ballets.

Throughout his career he kept faith with his classical formation. He married to it a strong theatricality and, underneath it all, a deep moral sensibility. In Kenneth MacMillan’s hands ballet was not a fairytale art, but a powerful mirror to human frailty.

Reference to https://www.kennethmacmillan.com

Kenneth MacMillan was one of the most groundbreaking figures in the dance world, and his legacy continues to shape ballet today. What made him extraordinary was not only his technical mastery but his determination to make ballet a true reflection of life—raw, complex, and emotionally charged. Unlike many of his contemporaries who favored tradition, MacMillan broke boundaries by weaving human struggles, psychological depth, and social realism into his choreography. His works often tackled difficult themes, pushing audiences to engage with dance as both art and storytelling. Rising from humble beginnings in Scotland, his journey to directing The Royal Ballet is a remarkable testament to resilience, passion, and vision. Collaborations with dancers and designers helped bring his bold imagination to life, leaving behind masterpieces like Romeo and Juliet and Song of the Earth. MacMillan remains a towering figure whose influence is still deeply felt.

The section detailing MacMillan’s transition from dancer to choreographer, particularly around “Somnambulism” and “Laiderette”, is both poignant and inspiring. It’s remarkable how his stage fright often seen as a career-ending affliction for performers became the catalyst for his greatest contributions to ballet. Rather than retreat, he redirected his creative energy, producing work that reflected psychological depth and raw emotion. It’s rare to see vulnerability turned so powerfully into innovation. His instinct to expose the darker, more complex layers of humanity through movement, while remaining grounded in classical form, set him apart in an art form often dominated by beauty alone. What support systems exist now for dancers dealing with similar stage-related anxieties, and do they foster the same kind of creative redirection?

That is a really good question Ravin. I know many people who don’t like the stage anxieties that many suffer from often end up being really good teachers and coaches. Not everybody can take the stress of performing every night.

Really liked this piece on Kenneth MacMillan — the guy wasn’t afraid to make ballet raw and real. It’s cool how he mixed classic style with real emotion instead of keeping everything polished and perfect. You can tell he cared more about telling a story than just showing technique, and that’s what makes his work still hit today.